Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction

Mastering the heart failure management NICE guidelines (NG206) is not just a box-ticking exercise for the UKMLA; it is fundamental to patient safety. Heart failure is the “final destination” for a multitude of cardiovascular pathologies, ranging from ischaemic heart disease and hypertension to valvular disorders and cardiomyopathies.

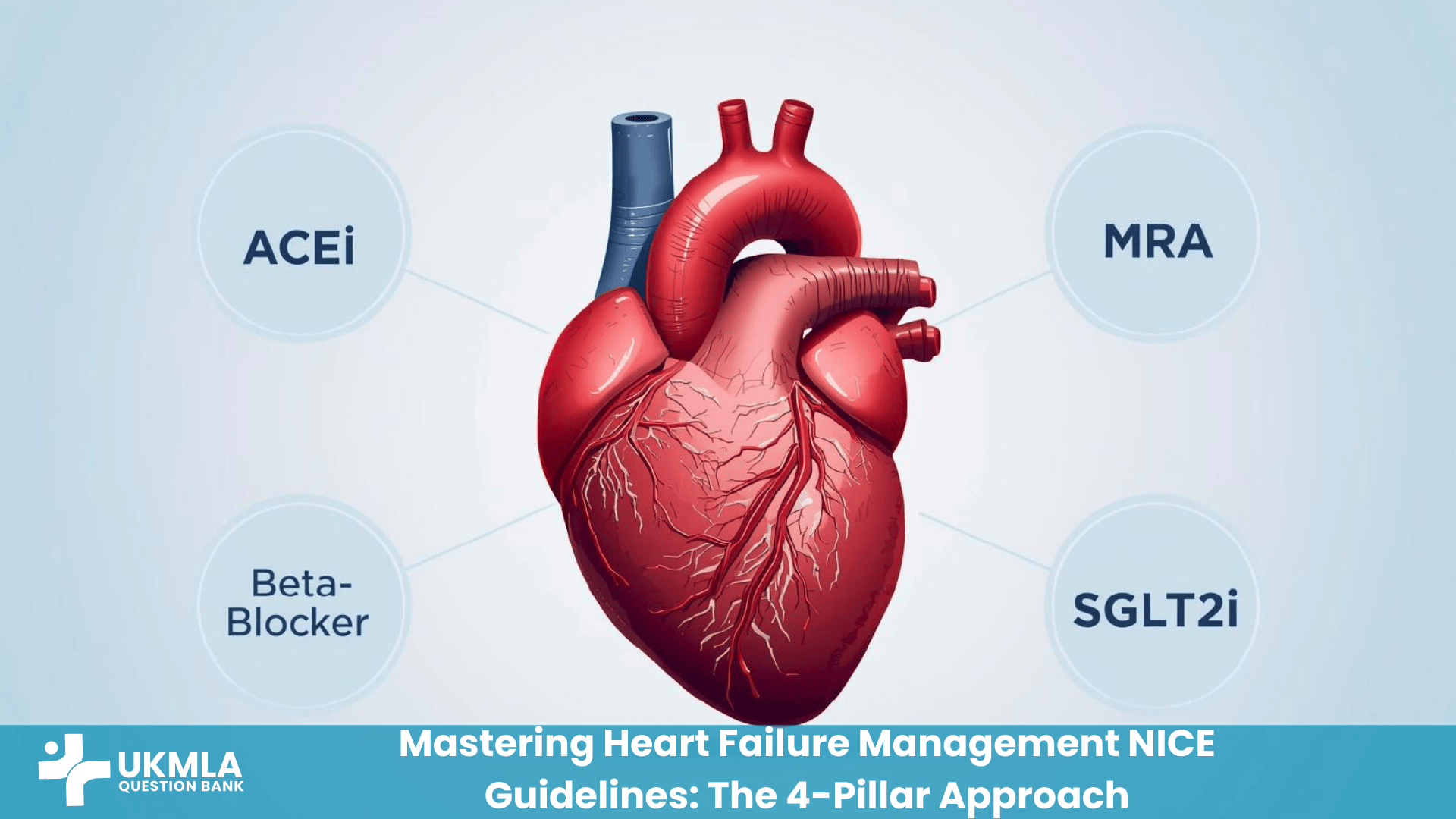

In the last five years, the landscape of heart failure treatment has undergone a paradigm shift. The traditional “stepwise” approach—starting one drug and waiting months to titrate—has been replaced by an aggressive strategy known as “Rapid Sequence Initiation.” We now have four drug classes—the “4 Pillars”—that must be initiated promptly to reduce mortality.

This comprehensive Pillar Post is your definitive resource. We will dissect the diagnostic pathway using NT-proBNP, explain the physiology behind the “4 Pillars,” provide specific scripts for CPSA counselling, and test your knowledge with clinical scenarios.

For a broader foundation before we begin, you may wish to review our Cardiology Essentials for UKMLA.

Key Takeaways

The “4 Pillars” are Mandatory: Treatment is no longer sequential; it requires rapid optimization of ACEi/ARB, Beta-Blockers, MRA, and SGLT2i.

The “Gateway” Test: NT-proBNP is the triage tool. Levels >2,000 ng/L require an urgent 2-week referral.

Diagnosis Requires Echo: You cannot diagnose Heart Failure without confirming reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF <40%) via Echocardiogram.

Symptom vs. Survival: Diuretics (Furosemide) improve symptoms but do not improve survival. The “4 Pillars” improve survival.

Sick Day Rules: Essential exam knowledge. Stop ACEi/ARBs, Diuretics, and SGLT2 inhibitors during acute dehydration (vomiting/diarrhoea).

Understanding the Pathophysiology

To manage heart failure effectively, you must understand what you are treating. Heart failure is defined as a complex clinical syndrome where the heart cannot pump sufficient blood to meet the metabolic needs of the body (HFrEF) or can only do so at elevated filling pressures (HFpEF).

The Neurohormonal Model

The body’s response to a failing heart is maladaptive. When cardiac output drops, the body attempts to compensate via two main systems:

Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS): Releases adrenaline/noradrenaline to increase heart rate and contractility. While this maintains perfusion in the short term, long-term activation is toxic to myocytes, increases oxygen demand, and causes arrhythmias.

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS): Activated by reduced renal perfusion. Angiotensin II causes vasoconstriction (increasing afterload), while Aldosterone causes fluid retention (increasing preload) and myocardial fibrosis.

The Treatment Logic: Every “Prognostic Drug” we use in the NICE NG206 Guideline aims to block these compensatory mechanisms. Beta-Blockers antagonise the SNS, while ACE Inhibitors, ARBs, and MRAs block the RAAS. SGLT2 Inhibitors have a more complex mechanism involving diuresis, metabolic efficiency, and anti-fibrosis.

The Diagnostic Pathway: NT-proBNP & Echo

In the UKMLA AKT, you will frequently be presented with a patient complaining of “breathlessness.” Differentiating heart failure from asthma, COPD, or anxiety relies on the NICE diagnostic pathway.

Step 1: Clinical History & Exam

Look for the cardinal symptoms of breathlessness (especially on exertion), orthopnoea (needing multiple pillows), and Paroxysmal Nocturnal Dyspnoea (PND), which is a highly specific sign of pulmonary oedema. On examination, look for signs of fluid overload such as an elevated JVP, bibasilar crackles, and pitting oedema.

Step 2: The “Gateway Test” – NT-proBNP

NICE recommends measuring N-terminal pro-B-type Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP) as the first-line investigation in primary care.

| NT-proBNP Level | NICE Recommendation | Timeline for Referral |

|---|---|---|

| > 2,000 ng/L | Urgent Referral | Specialist Assessment & Echo within 2 weeks. |

| 400 – 2,000 ng/L | Routine Referral | Specialist Assessment & Echo within 6 weeks. |

| < 400 ng/L | Heart Failure Unlikely | Investigate other causes (e.g., Spirometry, D-Dimer). |

Important Note: NT-proBNP is sensitive but not specific. False positives can occur in patients aged >75, those with Atrial Fibrillation, Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), or Sepsis. Conversely, obesity can cause false negatives as adipose tissue degrades natriuretic peptides. Learn more about interpreting these values in our guide to Interpreting Clinical Data.

Step 3: The 12-Lead ECG

An ECG should be performed in all patients. A completely normal ECG makes heart failure unlikely (Negative Predictive Value >90%). You are looking for pathological Q waves, Left Ventricular Hypertrophy, Atrial Fibrillation, or Left Bundle Branch Block (LBBB), which is crucial for device therapy decisions.

Classification: HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF

Once the Echocardiogram is performed, the patient is classified based on their Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF). This number dictates which drugs you are legally and clinically allowed to prescribe.

Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF): Defined as an LVEF ≤ 40%. This is the group with the most evidence-based treatment options, and the “4 Pillars” apply strictly here.

Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFmrEF): Defined as an LVEF of 41% – 49%. This is a grey area, but these patients are usually managed similarly to HFrEF.

Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF): Defined as an LVEF ≥ 50%. Previously called “Diastolic Heart Failure,” the heart pumps well but is stiff and relaxes poorly. Management is limited to SGLT2 Inhibitors and Diuretics, as ACEi/BB/MRA have no confirmed mortality benefit.

The “4 Pillars” of Management (HFrEF)

For patients with HFrEF, NICE NG206 mandates Prognostic Medical Therapy. These drugs modify the disease process and extend life. The 2026 standard is to initiate all four classes as quickly as possible.

Pillar 1: ACE Inhibitors (or ARBs)

First-line options include Ramipril, Enalapril, or Lisinopril. They work by blocking Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, preventing the formation of Angiotensin II, which vasodilates the vasculature and reduces cardiac afterload. Treatment should start at a low dose (e.g., Ramipril 1.25mg) and double every 2 weeks. You must check U&Es (Renal Function) 1-2 weeks after every dose increase; a Creatinine rise of <30% or Potassium < 5.5 mmol/L is acceptable. If a dry cough develops, switch to an ARB (Candesartan/Valsartan). For more details, see Prescribing Safety.

Pillar 2: Beta-Blockers

Licensed options are Bisoprolol, Carvedilol, and Nebivolol. These drugs reduce myocardial oxygen demand and protect against arrhythmias. The “Golden Rule” for the exam is to never start a Beta-Blocker in a patient who is acutely “wet” (fluid overloaded). As negative inotropes, they can precipitate cardiogenic shock in decompensated patients. You must stabilise the patient with diuretics first, then start low and slow.

Pillar 3: Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRA)

Spironolactone and Eplerenone block aldosterone receptors, reducing cardiac fibrosis and fluid retention. The major adverse effect is hyperkalaemia, so potassium must be monitored rigorously. Additionally, Spironolactone can block androgen receptors causing gynaecomastia (painful breast tissue) in men; if this occurs, switch to Eplerenone, which is selective and avoids this side effect.

Pillar 4: SGLT2 Inhibitors

Dapagliflozin and Empagliflozin represent the biggest revolution in heart failure care. Originally diabetes drugs, they are now mandatory for all HFrEF patients, even if they do not have diabetes. They offer a rapid reduction in hospitalisation risk within 28 days. However, they are generally contraindicated in Type 1 Diabetes (due to DKA risk), pregnancy, and severe renal impairment (eGFR < 20 ml/min).

Symptom Control: The Art of Diuretics

While the “4 Pillars” save lives, they take weeks to make the patient feel better. Loop Diuretics (Furosemide/Bumetanide) are the key to immediate symptom relief. The goal is to achieve and maintain “dry weight” (euvolemia). Crucially for the exam, remember that diuretics do NOT improve mortality; they are purely for symptom control. Patients should weigh themselves daily, as a sudden gain of >2kg in 2 days suggests fluid retention requiring a temporary dose increase. For management strategies, see Understanding Fluid Balance Charts.

Advanced Therapies: IV Iron, Devices & Digoxin

When optimal medical therapy (OMT) is not enough, or specific comorbidities exist, we escalate.

Device Therapy (ICD & CRT)

If LVEF remains ≤ 35% despite OMT for 3 months, you must assess the ECG QRS Duration to determine the need for an implantable device.

| QRS Duration | Pathophysiology | Recommended Device |

|---|---|---|

| < 130 ms (Narrow) | Risk of Arrhythmic Death (VT/VF) | ICD (Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator) |

| ≥ 130 ms (Wide) | Dyssynchrony (LBBB) | CRT (Cardiac Resynchronisation Therapy) |

CPSA Corner: Counselling & Sick Day Rules

In the CPSA, use simple analogies and avoid jargon. Refer patients to British Heart Foundation resources for visuals.

Sick Day Rules Script

“Mr Jones, these tablets are powerful and affect how your kidneys handle water. If you get a stomach bug with vomiting or diarrhoea, or a high fever where you are sweating a lot, you could get dehydrated. If this happens, you must temporarily stop the ‘DAMN’ medicines until you are eating and drinking normally again.”

The “DAMN” Drugs:

D – Diuretics (Furosemide)

A – ACE Inhibitors / ARBs

M – Metformin / MRA (Spironolactone)

N – NSAIDs (Should be avoided generally)

Driving & Employment (DVLA Rules)

For Group 1 (Car/Motorcycle) drivers, no notification to the DVLA is needed unless symptoms occur at rest or while driving (distracting symptoms). However, if the patient is symptomatic, they must stop driving until stable. For Group 2 (Bus/Lorry) drivers, they must notify the DVLA and are disqualified if their LVEF is < 40% or if they are symptomatic (NYHA Class III or IV).

Clinical Scenarios: Putting it into Practice

Scenario A: The “Wet” Patient A 65-year-old male with known HFrEF presents with increasing breathlessness, basal crackles, and ankle oedema. His BP is 130/80. He is currently on Ramipril and Bisoprolol. The correct management is to increase his Furosemide to diurese him to dry weight. You should NOT increase the Bisoprolol dose at this time, as increasing beta-blockade in an acute exacerbation can worsen failure. You should continue the Ramipril unless renal function is critically deranged.

Scenario B: The “Renal” Dilemma A 70-year-old female starts Ramipril 2.5mg. Two weeks later, her Creatinine rises from 100 to 125 umol/L, and her Potassium is 5.2 mmol/L. The rise in Creatinine is 25%, which is within the acceptable limit (<30%). The action is to continue the Ramipril and re-check in one week. Do not stop the drug. In heart failure, we tolerate mild renal impairment to secure the long-term cardiac benefit.

Practice Exercise: Test Your Knowledge

Question 1: A 58-year-old man with HFrEF (LVEF 30%) is on Ramipril, Bisoprolol, and Furosemide. He remains breathless on exertion. QRS duration is 100ms. What is the most appropriate next step?

A) Add Digoxin

B) Refer for CRT-D

C) Add Spironolactone

D) Stop Ramipril

E) Add Amlodipine

Correct Answer: C) Add Spironolactone. He is currently on 2 pillars. The next logical step is to add the 3rd pillar (MRA) or an SGLT2 inhibitor. Cardiac Resynchronisation Therapy (CRT) is not indicated yet because his QRS is narrow (<130ms) and his medical therapy is not yet optimal.

Question 2: A patient taking Spironolactone develops painful breast tissue. Which drug should replace it?

A) Furosemide

B) Eplerenone

C) Candesartan

D) Bendroflumethiazide

Correct Answer: B) Eplerenone. Spironolactone is a non-selective aldosterone antagonist that can block androgen receptors, leading to gynaecomastia. Eplerenone is a selective MRA that does not affect androgen receptors and avoids this specific side effect.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about Heart Failure Management NICE

Sacubitril/Valsartan is an ARNI (Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor) recommended by NICE NG206 as a replacement for an ACE Inhibitor (or ARB) if the patient remains symptomatic (NYHA Class II–IV) despite optimal medical therapy and has an LVEF < 35%. The drug works by simultaneously blocking the RAAS system and preventing the breakdown of beneficial natriuretic peptides, offering a significant mortality benefit. However, a critical safety rule for the UKMLA is the mandatory 36-hour washout period after stopping an ACE inhibitor before starting Entresto to prevent life-threatening angioedema caused by bradykinin accumulation.

Generally, the answer is no. While SGLT2 inhibitors (Dapagliflozin/Empagliflozin) are mandatory for heart failure in non-diabetics and Type 2 diabetics, they carry a high risk of Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) in Type 1 diabetics. They can cause “Euglycaemic DKA,” where the patient is in ketoacidosis but has normal blood sugar levels, leading to delayed diagnosis. For UKMLA purposes, consider Type 1 Diabetes a contraindication unless the question specifies “under strict specialist supervision.”

NSAIDs (Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Diclofenac) are dangerous due to their effect on renal hemodynamics. Prostaglandins are required to keep the afferent arteriole of the kidney dilated to maintain blood flow. NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandins, causing afferent vasoconstriction. If a patient is on an ACE inhibitor (which dilates the efferent arteriole) and a Diuretic (which reduces volume), adding an NSAID creates a “Triple Whammy” that crashes the Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR), causes acute kidney injury, and leads to sodium retention that precipitates acute pulmonary oedema.

Differentiating “Cardiac Asthma” from COPD relies on specific history and investigation cues. A history of Paroxysmal Nocturnal Dyspnoea (PND) and Orthopnoea strongly suggests Heart Failure, while a heavy smoking history and productive cough suggest COPD. On Chest X-Ray, heart failure shows cardiomegaly, upper lobe diversion, and Kerley B lines, whereas COPD shows hyperinflated lungs and flattened diaphragms. Furthermore, arterial blood gases in COPD exacerbations often show Respiratory Acidosis (CO2 retention), while cardiogenic shock typically shows Metabolic Acidosis (Lactate accumulation due to poor perfusion).

In HFrEF, we tolerate much lower blood pressures than in the general population because the priority is to maintain the highest tolerated dose of the “4 Pillars,” not to hit a specific BP number. A systolic BP of 90–100 mmHg is often acceptable if the patient is asymptomatic (no dizziness, syncope, or falls). For the exam, remember that you should not stop life-saving prognostic drugs like Beta-blockers just because the BP is 95/60 mmHg, provided the patient feels well.

Yes, but it is a specific niche recommendation for patients of African or Caribbean family origin who have moderate-to-severe heart failure (NYHA III/IV) despite taking all other standard therapies. Evidence suggests this specific population responds better to nitric oxide donors. It can also be used as an alternative for patients who physically cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors or ARBs due to severe renal failure or persistent hyperkalaemia.

You should always refer every single patient discharged from the hospital with a diagnosis of Heart Failure. High-quality evidence shows that cardiac rehabilitation significantly reduces hospital readmissions and improves quality of life. It is not just an exercise class; it includes vital education on diet (low salt), fluid management, and psychological support, making it a mandatory part of holistic care.

Fitness to fly depends on the patient’s NYHA functional class. Patients in NYHA Class I & II (mild symptoms) can fly without restrictions. Patients in NYHA Class III (breathless on mild exertion) can fly but may require in-flight oxygen and airport assistance. However, patients in NYHA Class IV (breathless at rest) are generally contraindicated from commercial flying because the cabin pressure at altitude reduces oxygen saturation slightly, which a failing heart cannot tolerate.

AF and Heart Failure are “twins” that worsen each other. The loss of the “atrial kick” (active atrial contraction) reduces cardiac output by approximately 20%, and a rapid ventricular rate prevents proper filling. Management involves mandatory stroke prevention with DOACs and rate control with Beta-blockers or Digoxin. If the heart failure is thought to be caused by the AF (Tachycardia-Induced Cardiomyopathy), restoring sinus rhythm via Cardioversion or Catheter Ablation becomes a priority.

Digoxin has a narrow therapeutic window, and toxicity is most often precipitated by hypokalaemia (often caused by the Furosemide the patient is also taking). The first signs are usually gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, anorexia). Visual disturbances, such as xanthopsia (yellow halos around lights) or blurred vision, are classic. Cardiac signs include almost any arrhythmia, but the “Reverse Tick” sign (ST depression) on ECG is characteristic, along with AV blocks or ventricular ectopics.

Conclusion

Heart Failure management has moved beyond simple symptom relief. The goal of the NICE NG206 guidelines is to modify the disease trajectory using the “4 Pillars”: ACEi/ARNI, Beta-Blockers, MRA, and SGLT2i.

For the UKMLA, remember the sequence:

Diagnose with NT-proBNP and Echo.

Classify by LVEF.

Initiate the 4 Pillars rapidly for HFrEF.

Manage fluid status with flexible diuretics.

Counsel on Sick Day Rules via the Pumping Marvellous app.

Mastering this pathway will ensure you are ready for both the AKT cardiology questions and the complex communication stations in the CPSA.